|

An example of a stablecoin peg from the now defunct FTX US [source]

|

This post is for anyone who is curious how cryptocurrency exchanges and stablecoins work behind the curtains. It's common knowledge that stablecoin issuers like Tether, Paxos, and Circle run pegs. What isn't commonly known is that crypto exchanges like Binance (and the now-failed FTX) also run their own versions of stablecoin pegs.

Stablecoin issuers like Tether anchor, or peg, the value of their tokens to $1 in fiat dollars, and use their dollar reserves to enforce that peg. Another way to think of the process of pegging is to take two heterogeneous things and use economic resources to make them homogeneous, or fungible, with each other in terms of price.

Exchanges such as Binance peg stablecoins in two ways:

1) Pegging multiple stablecoins to each other

Most crypto exchanges do not peg stablecoins to other stablecoins. They let the price of stablecoins float, or fluctuate, against each other. That is, if you deposit 1 unit of USD Coin and 1 unit of Binance USD to an exchange, you don't get credited with $2. You get credited for a single unit of each heterogeneous stablecoin. The exchange rate between these two coins fluctuates on the exchange according to supply and demand.

FTX was the first exchange to move from floating to pegging stablecoins. Binance followed FTX when it adopted its own pegging mechanism this fall. Basically, Binance promises to treat heterogeneous stablecoins in a homogeneous manner, by allowing customers to deposit any amount of approved stablecoins at the exact same price; $1. Customers can also withdraw whatever stablecoin they wish from Binance at $1, in any amount.

The approved basket for both Binance and FTX includes USDP, USD Coin, Binance USD, TrueUSD, but not Tether.*

By promising to process all stablecoin transactions at a uniform rate, the former-FTX and Binance shifted from the traditionally passive let 'em float practice of dealing in stablecoins to setting, or administering, stablecoin prices.

Pegging a basket of stablecoins is more complicated than letting them float. It requires having sufficient reserves of each stablecoin in order to defend the fixed price. If Binance users all want to suddenly withdraw a certain brand of stablecoin, but Binance runs out of reserves of that type, then it'll have to temporarily suspend its peg, at least until it can acquire more of the in-demand stablecoin.

It appears that this was exactly what happened to Binance earlier this week. When customers wanted to withdraw large amounts of USD Coin, Binance ran out and had to temporarily suspend USD Coin withdrawals. "In the meantime, feel free to withdraw any other stable coin, BUSD, USDT, etc." wrote the exchange's owner, Changpeng Zhao.

Later, Binance sent a massive chunk of its own Binance USD hoard to the issuer, Paxos Trust, for redemption into fiat US dollars, before turning those dollars back into USD Coin (by going through Circle, USD Coin's issuer). Binance's coffers refilled, it could thus reestablish its peg.

Let's move onto the second type of peg that exchanges set.

2) Pegging the same stablecoin on different chains to each other

Stablecoins of the same brand exist on different blockchains. Tether, for instance, exists on both the Tron and Ethereum blockchains, as well as a host of other chains. The same goes for USD Coin.

Exchanges always peg a given stablecoin across its multiple instances.

What I mean by that is exchanges allows customers to deposit any amount of Tether (on Tron) or Tether (on Ethereum), and the exchange will treat those heterogeneous deposits as a single homogeneous Tether unit. And when customers want to withdraw, they can withdraw any amount of Tethers—Tron or Ethereum—from that pot at the same fixed price.

But Tether-TRX and Tether-ERC are not homogeneous tokens. They are very different beasts, with different characteristics, use cases, and demographics. Exchanges could in principal treat each instance of Tether separately, letting them float against each other. So in a given minute a single Tether-on-Tron token might be worth 1.001 Tether-on-Ethereum token, and the next 0.998 according to supply and demand.

Exchanges don't do this. They peg the two instances of Tether. Customers take this for granted, but it's thanks to these exchanges' pegs that a customer can deposit 1 million Ethereum-based Tether onto an exchange and three seconds later withdraw 1 million Tron-based Tether, all at a convenient fixed price rather than a floating one.

To maintain these intra-stablecoins pegs, exchanges must have sufficient reserves of all blockchain flavors of Tether. (And all flavors of USD Coin and Binance USD, too.) Sometimes you'll see an exchange accumulating too much of one type of Tether while running out of the other type, and it'll engage in a swap with in order to rebalance its reserves.

This is likely what happened to Binance this week, when it swapped a massive 3 billion Tether-on-Tron into 3 billion Tether-on-Ethereum. Too many customers we're withdrawing Ethereum-based Tether, and so it had to rebalance its reserves:

In the next section, I'm going to sketch out the bigger picture.

Crypto exchanges as stablecoin watchdogs

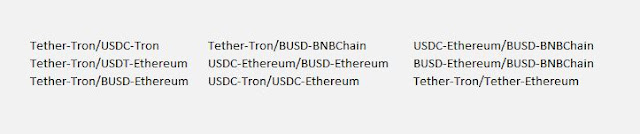

I generally think it's a good idea for exchanges to treat stablecoins homogeneously, both in the first way (pegging stablecoins to other stablecoins) and the second way (pegging a stablecoins across its multiple instance). Doing so makes things easier for customers. Could you imagine, for instance, if exchanges didn't peg the different flavors of Tether, USDC, and BUSD? You'd end up with dozens of different stablecoin exchange rates:

But creating a stablecoin standard isn't costless. Exchanges need to devote resources to constant management of their reserves. If they make a mistake, as the case with Binance this week, they end up looking bad.

Pegging stablecoin to other stablecoins opens exchanges up to credit risk, too. If a given stablecoin suddenly collapses, exchanges that let stablecoins float needn't worry about a thing. They can continue accepting deposits of the failed coin at its market price.

Not so exchanges that administer stablecoin prices. Traders will rapidly send the now worthless stablecoin to any exchange that is still pegging it at $1. To prevent the danger of becoming a sop for failed stablecoins, exchanges like Binance have to constantly surveil the stablecoins in their basket for credit risk.

In the grand scheme of things, this is probably a good thing. It deputizes exchanges as stablecoin watchdogs. Since exchanges have significant resources and insider knowledge, they are probably better at analyzing stablecoins for credit risk than outsiders like myself. Binance's basket of fungible stablecoins becomes a signal to the market of what stablecoins are safe.

We already saw an example of this stablecoin watchdog role in action not too long ago. A stablecoin called HUSD began to wobble in August:

After regaining its peg, HUSD outright failed in October, collapsing from $1 to a few pennies.

The collapse seemed to come out of the blue. No so. FTX, the first exchange to peg stablecoins, had quietly removed HUSD from its stablecoin basket in early August, tipping anyone who was observing that something was up.

However, if there are ecosystem-wide benefits to exchange stablecoin pegs, there are also drawbacks. Exchanges that treat stablecoins homogeneously (and thus take on credit risk) may do a poor job of it, and thus the fallout from a major stablecoin failure could spread to exchanges, an isolated failure becoming a systemic one. The benefit of the traditional practice of letting stablecoins float is that it renders the crypto exchange system more immune to the systemic risk stemming from the failure of a stablecoin.

*Why is Tether not included in these stablecoin baskets? One theory is that exchanges like Binance and FTX are acting as watchdogs and don't want to include Tether because of its unique credit risk. That's possible, but I think it's more likely that they don't want to include Tether because managing Tether reserves is too costly. This cost arises from the fact that Tether charges a 0.1% fee on all withdrawals and redemptions of Tether tokens. Other stablecoins provide this service for free. As long as this fee exists, it's just not worth it for exchanges to include Tether in their basket.