Back in 2018 I wrote about the controversy over the constant stream of bitcoin ETF denials emanating from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). And my conclusion then was: "further rejections likely." My conclusion in 2023 is the same. Even with Wall Street-giant Blackrock entering the scene with a proposed Nasdaq-listed iShares Bitcoin ETF, nothing has changed: a bitcoin ETF probably probably won't get approved.

The FT says that the big difference this time around is that Blackrock will enter into a "surveillance-sharing agreement with an operator of a United States-based spot trading platform for bitcoin." It's pretty clear that this agreement will be with Coinbase, the U.S.'s largest crypto market.

This may sound convincing, but the idea that Blackrock is the first potential bitcoin ETF issuer to enter into surveillance-sharing agreement with a U.S. exchange is wrong. It's an old tactic, one that hasn't worked to-date.

When the Winklevoss twins famously tried to launch their bitcoin ETF on the Bats BZX exchange many years ago, part of their (modified) proposal involved BZX entering into a surveillance-sharing agreement with the Gemini Exchange, a U.S. crypto exchange. But the SEC didn't see this as adequate in 2018, so it's not apparent to me why that approach would be adequate now.

Let's back up. Why surveillance sharing agreements?

I got into this in more detail five years ago, but here's a quick explanation. When an exchange lists an ETF, particularly a commodity-based one, that ETF is typically underpinned by some sort of commodity, say lumber or copper, that gets traded on another exchange (or set of exchanges). The SEC believes that a mutual agreement to share information between the relevant exchanges is key to preventing fraudulent and manipulative acts. For example, if one exchange serves as a venue for trading bananas, and another exchange wants to list a banana ETF, the SEC will only approve said ETF if the listing exchange shows that it can monitor the underlying spot banana exchange to catch manipulators, the end goal being to protect investors.

The Winklevoss's earlier attempt to prevent manipulation through surveillance sharing with Gemini wasn't deemed sufficient by the SEC, for two reasons. Gemini was neither significant (i.e. "big relative to the overall market"), nor was it regulated as a national exchange.

Fast forward to 2023. In its proposal, Blackrock is essentially swapping out Gemini with Coinbase, by having Nasdaq, the exchange that will list the iShares Bitcoin ETF, share surveillance with Coinbase. But unfortunately for Blackrock, nothing has changed. First, much like Gemini, Coinbase isn't a regulated exchange. Secondly, Coinbase isn't all that big in the global scheme of things, especially compared to global titan Binance, an offshore exchange. So I doubt that a surveillance sharing agreement with Coinbase will get Blackrock's proposal over the line.

A second tactic that Blackrock is using to get SEC approval is to establish another surveillance sharing agreement with a regulated futures exchange, one that offers bitcoin contracts. As I explained in my 2018 article, this is how the massive SPDR Gold ETF got approved a few decades ago. When trading in a commodity occurs informally, say via over-the-counter markets (as it does with gold), and it's not possible for an exchange that lists an ETF to ink surveillance sharing agreements, then the SEC may accept an agreement with a futures exchange as a substitute, in SPDR's case the NYMEX exchange.

In Blackrock's case, it has chosen to have Nasdaq, the exchange on which it will list, mutully share information with CME futures exchange, which lists bitcoin futures.

At first blush, Blackrock seems on the right track. The CME ticks the "regulated" column, unlike Coinbase. What about the "significant" column? The CME's open interest of around $1.5-2.0 billion is about half of Binance's $3-4 billion in futures open interest (and just a small fraction of the $10 billion combined total of Binance and all other unregulated offshore exchanges), so I'm not sure how the CME will qualify as big enough. (I get this data from The Block.) Put differently, if you wanted to manipulate the price of bitcoin using futures, you'd probably be able to do a fine job of it via Binance's futures market, and so Blackrock's surveillance sharing agreement with the CME just won't be all that effective.

In any case, this particular gambit has been tried before, and it hasn't worked. A parade of ETFs have tried to use a CME surveillance sharing agreement as their ticket to SEC approval, many using in-depth statistical analysis showing why the CME qualifies as "significant," and none have convinced the SEC, so it's not evident why Blackrock is special.

If Blackrock's iShares Bitcoin ETF isn't going to get approved, what needs to happen to get a bitcoin ETF over the line?

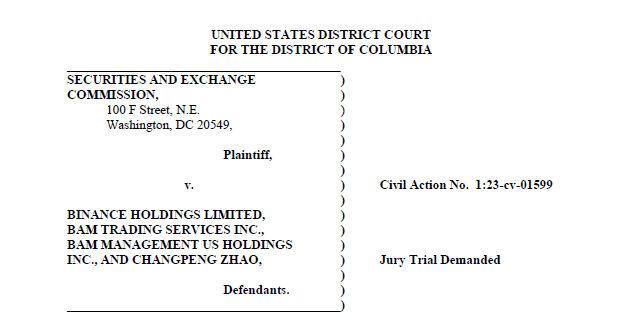

In my opinion, the unregulated offshore market needs to die. Much of crypto price discovery (and thus potential manipulation) occurs in offshore markets, both on the spot and futures side. Given the logic that the SEC has used up till now, Binance needs to go bust, and kosher venues need to take its place, before a U.S. bitcoin ETF get approved, because it's only then that a majority of bitcoin trading will migrate to venues that tick both the SEC's "regulated" and "significant" requirements.