Earlier this month the Federal Reserve introduced its new instant retail payments system, FedNow. This is actually the U.S.'s second real-time retail settlement system. The first, The Clearing House's Real Time Payments Network, or RTP, opened for business back in 2017.

As FedNow and RTP develop over the next few years, a good way to gauge their performance will be to look to the UK, which provides a useful blueprint of a successful rollout of real-time retail payments, one that the U.S. would surely like to emulate.

The UK introduced its Faster Payments real-time system in 2008, almost ten years ahead of the American roll-out of RTP. Prior to 2008, payments made by U.K. retail bank customers entirely relied on a piece of infrastructure called Bacs, built back in 1968 and originally dubbed the Bankers’ Automated Clearing System. Much like the automated clearing house (ACH) payments, the go-to U.S. option for retail payments, Bacs payments are not immediate, often taking several days to settle.

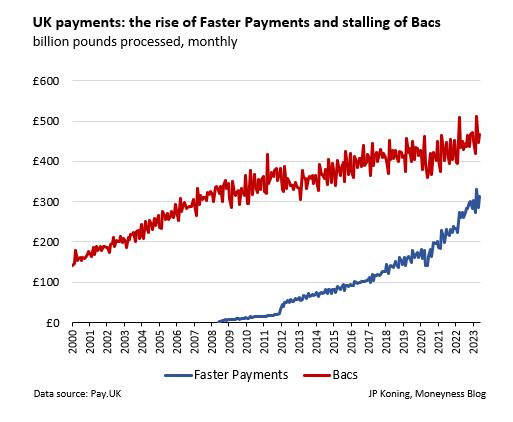

Below is a chart of the total value of payments processed by Faster Payments and Bacs over time:

As you can see, the value of Bacs payments was advancing at a brisk 10% pace until Faster Payments landed in 2008, at which point they immediately slowed to a lethargic 2-3%, in some years not growing at all. The Faster Payments scheme, which is currently expanding at a healthy clip of 15-20% each year, is set to surpass Bacs by 2025 or 2026.

A steady eclipsing of the slower network is what should ideally happen in the U.S. as consumers switch from ACH over to useful (and often crucial) real-time FedNow or RTP payments. Mind you, we shouldn't expect ACH to be entirely replaced. It's still more efficient to use slower systems to settle non-time sensitive payments.

Unfortunately, the U.S. is already far behind the timetable set by the UK, and is unlikely to catch up.

Let's take a look at RTP, which is now in its seventh year of operations. When the UK's Faster Payments system was in its seventh year, it was already processing around £225 billion worth of payments per quarter, a hefty 20% of the value then flowing through Bacs. Alas, as the chart below illustrates, the blazing-fast RTP network processed $25 billion worth of payments in the first quarter of 2023, just 0.1% of the $19.7 trillion load processed by U.S.'s ACH network. That's next to nothing.

|

| Source: The Clearing House |

I don't see why FedNow will prove anymore successful than RTP in driving real-time payments, since it offers no real advantages over its competitor. (In fact, the second network may even slow down the overall growth rate of real-time payments, as I'll show further down.)

I count two reasons why the uptake of real-time payments in the U.S. has lagged U.K., and why this under-performance will only continue, even with FedNow's introduction.

1. The U.S. has over 9,000 banks, thrifts, and credit unions. By contrast, the UK has only 357 banks and building societies. Not only are there fewer UK banks, the UK's top-5 banks are more concentrated, controlling around 60% of all banking assets compared to the U.S. top-5, which control just 50%.

The advantage of having fewer, more concentrated banks is that it makes it easier for the banking system to coordinate a shift onto a new network. When Faster Payments started, for instance, it enjoyed a huge vanguard group with all of the UK's biggest banks participating, including NatWest, Barclays, Lloyds, and HSBC. Not so with FedNow, which has only signed up 41 of America's 9,000 financial institutions, and is missing top-10 banks like Bank of America, PNC, Truist and TD.

(Those with long memories will recall that this vanguard group problem is also why Canada's e-Transfer service has grown so much faster than U.S.'s Zelle.)

2. Further complicating adoption is that fact that while the UK had just one instant network, Faster Payments, the U.S. has two real-time networks, FedNow and RTP. These two networks are not interoperable with each other. A bank that wants to offer real-time payments to its customers may choose to delay incurring the set-up costs of joining either of the two networks, until a definite favorite has emerged. But this collective hesitation will prevent real-time payments from ever being adopted in the first place.

To sum up, the road to real-time settlement systems in the U.S. has been a long one. Whereas the UK introduced Faster Payments in 2008, it took another decade for RTP to be built, and five years on top of that for FedNow. Alas, the path to actual usage of these new real-time systems will be even slower, given the diffuse nature of the U.S. banking system and the hesitation effect that comes with having two competing networks.