|

| Berkshire Hathaway annual general meeting |

When you purchase a share you're not only getting the opportunity to make some extra cash. You're also buying a vote. Put differently, a share offers two different features: a) a claim on earnings and b) the right to exercise partial control over the corporation.*

Why not separate the two features and put each of them up for sale? Let's have one market for corporate votes, and a separate one for corporate returns.

Here's how it would work. Imagine you want to buy some Microsoft shares but don't care to participate in the governance of Microsoft. The quoted price on the market, $44.93, is for a whole share of Microsoft, both its attached voting rights and its capitalized return. So you buy 500 whole shares for $27,465.

Next you turn to the parallel public voting market. Microsoft votes are trading for around 25 cents each, say. You 'detach' each of the 500 votes from the shares you've just bought and sell those votes for 25 cents each in the voting market for a combined $125. Not a bad day's work. In selling the votes that you never wanted anyways you've defrayed your initial purchase cost.

A few years later you decide to get out of Microsoft. One way is to find a set of buyers who, like yourself, don't care to vote, and sell the voteless shares directly to them. Alternatively you can repurchase the 500 votes in the voting market, reattach them to the shares, and sell them in the whole share market.

Here's another hypothetical: imagine that you have 500 shares of Microsoft but feel that it's your destiny to have a much more active role in Microsoft governance than your 500 votes would otherwise provide. Say you'd like ten times the votes, or 5,000 votes. To amass that quantity of votes it would normally cost you the price of 4,500 additional shares at $44.93 each, or about $207,000, but that's far out of your league. That's where the market for Microsoft votes comes in. For a mere $1125 you can pick up 4,500 detached votes, assuming they trade at 25 cents each. Without having stumped up too much capital, you've become a much more formidable shareholder activist.

So why have a market for corporate votes?

According to Broadridge, some 70% of retail shares go unvoted. Participation rates are better on the institutional front where some 90% of institutionally-owned shares are voted, but this is due to a legally-mandated fiduciary responsibility to vote. The responsibility for voting these shares is usually outsourced to a proxy advisory company like ISS which, according to one account, advised on over 50% of corporate votes cast in the world. ISS's success is due in part to the fact that institutional shareholders have scarce resources, most of which are ready allocated to searching for new investments and monitoring existing ones. They can't spare the cost of setting up expertise in corporate governance.

So to a large proportion of retail and institutional investors, votes represent little more than a nuisance. In order to play the stock market game, these investors hold their noses and pony up enough cash to buy a share and its combined vote; but they'd really be quite happy if they didn't have to buy the latter, especially if it meant reducing their overall costs.

If those who view votes as a nuisance comprise the sell side of the corporate vote market, then the buy side would be comprised of a cadre of institutional investors who specialize in corporate governance and shareholder activism. Activist investors, say someone like Bill Ackman, have developed expertise and a set of practices that allow them to efficiently put votes to work, instituting change in a company's structure or management in order to make it more profitable. They place a much higher marginal value on the votes attached to shares than the majority of their not-so-active colleagues.

A market in corporate shares would allow both the apathetic and the active to meet, with the final result being a more efficient allocation of returns and voting rights.

What I'm proposing may sound a bit sci fi, but what if I told you that such a thing already exists?

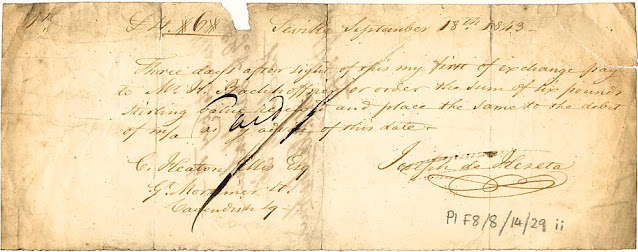

The fact is that we already have an informal market of sorts in corporate votes. In Canada, for instance, firms often issue both non-voting, voting shares, and multiple voting shares. In the U.S. the practice is less common, one example being Google which has issued 'A' shares with one vote apiece; 'B' shares with ten votes each; and 'C' shares with no votes. Or consider Warren Buffet's Berkshire Hathaway. An owner of $10,000 worth of Berkshire Class B shares has 0.15% of the votes that an owner of $10,000 worth of Class A shares has.

When companies have dual share structures, to buy votes, an investor need only short the non-voting shares in order to fund a long position in the voting class. And to sell votes, do the opposite. The cost one would incur on this transaction indicates the dollar value the market places on the right to vote.** Canadian readers may well remember that Mason Capital engaged in this strategy with Telus shares back in 2012 when it purchased Telus voting shares and shorted its non-voting shares.

But there's a more interesting way to get one's hands on extra votes. Start by borrowing whole shares just prior to a vote, much like a short seller borrows shares prior to selling them short. Rather than selling the borrowed shares, however, an activist holds them in order to exercise their voting rights, then returns the shares soon after the vote to the lender. The cost they'll pay on this round trip represents the price of a vote. From the perspective of the the owner who has lent the shares out, they require a high enough fee in order to compensate them for having foregone their franchise over the interim.

For instance, in 2002, Laxey Partners, a hedge fund, held about 1% of the shares of British Land, a major U.K. property company. However, on the day of British Land's shareholder meeting Laxey controlled 9% of the votes, note Hu and Black, all the better to support a proposal to dismember British Land. Just before the record date, Laxey had borrowed 8% of British Land's shares.

The term used for having more votes than shares is empty voting. Someone with 5,000 votes and only 500 shares is in possession of 4,500 empty votes, since those 4,500 votes have been 'emptied' of their economic interest. Empty voting is welfare-improving when an activist investor with a good plan acquires votes beyond his or her economic interest in order to ensure that their plan is adopted. However, at the extreme, empty voting can get downright spooky. Consider a fund that has amassed short position in a stock (ie. it expects the shares to fall in value) while building a long position in votes. Perversely, this 'rogue' fund could very well use their franchise to implement changes that hurt the firm, not help it, and thereby bolster their short position.

Hu and Black, who refer to the decoupling of votes and economic interest as "the new vote buying", note that vote transactions are often hidden from the public and regulators. All the more reason to have a formal market for votes as described at the start of this post rather than the terribly confusing one that already exists. A transparent price for voting would help reveal rogue attempts to corral large empty voting positions. Those activists who truly want to create shareholder friendly changes would be able to accurately price out the cost of resisting the rogues.

And all those investors who are too unsophisticated to understand the murky world of stock lending, ie. retail investors, would be able to use widely-disseminated prices to better gauge the value of their vote and access an open market for the transferral of those votes.

* A share also offers a third feature, a liquidity return. I've pointed this out many times before. For the sake of this post, we'll ignore the liquidity portion.

** Strictly speaking, if the non-voting shares you short also happen to be less liquid than the voting shares you are long, then you are not only buying votes, you're also buying liquidity. But as I pointed out in the above bullet point, I'm ignoring liquidity returns for the sake of simplicity.

*** I have an ulterior motive for a market for corporate votes. I think the phenomenon of naked shorting doesn't deserve the vilification it receives in the press and on blogs. In fact, naked shorting is a necessary part of ensuring that liquidity premia on equities are kept at market clearing prices. The proper functioning of what I've referred to as the 'moneyness market' depends on naked shorting. The problem with a naked short is that the resulting synthetic security that the short seller creates doesn't have a vote. It is a non-standard instrument. With the existence of a corporate vote market, a naked short seller might re-standardize the instrument by purchasing a vote and attaching it to the IOU that they've created via their naked short. I do plan on writing about this next month, so if you didn't understand my point, just wait.

Links:

Hu & Black, 2006. The New Vote Buying: Empty Voting and Hidden (Morphable) Ownership

Aggarwal, Saffi, & Sturgess, 2010. Does Proxy Voting Affect the Supply and/or Demand for Securities Lending

Financial Post, November 2012. Empty Voting Clouds Shareholder Rights Law

Black, 2012. Equity Decoupling and Empty Voting: The Telus Zero-Premium Share Swap

Brav & Mathews, 2011. Empty voting and the efficiency of corporate governance