[This article was published last week in CoinDesk.]

The Pluses and Minuses of Regulating Crypto as Gambling

In the wake of FTX's shocking collapse, a new idea for regulating crypto has begun to take form: Let's regulate crypto like we regulate gambling.

Todd Baker, a Senior Fellow at the Richman Center for Business, Law and Public Policy at Columbia University, recently writes that "crypto trading should be regulated for what it is – gambling emulating finance and not what its advocates say it is or what people believe it to be."

The European Central Bank's Fabio Panetta suggests that "regulation should acknowledge the speculative nature of unbacked cryptos and treat them as gambling activities." And here is a recent American Banker article on the topic.

There are some good aspects to the idea of regulating crypto as gambling, and some bad.

First, the bad.

Crypto is too diverse for one regulatory framework

Any claim that we should regulate crypto as X isn't very helpful, and that's because the stuff we call "crypto" has long ceased to be a single-issue product that can be conveniently boxed into any one framework. Maybe back in 2012 and 2013 it could have been. And gambling might very well have been the best fit back then.

But, at its core, crypto consists of a bunch of programmable databases, which means they can host all sorts of applications – not just gambling applications. Zoom forward to 2022 and the range of activities occurring in the crypto space has become quite broad and diverse.

Take MakerDAO, for instance. MakerDAO is built on a blockchain, and so it falls under the “crypto” umbrella. But it isn't a gambling product. Functionally, MakerDAO is a bank that makes loans by issuing deposits in the form of dai (DAI), a stablecoin.

To make things more complicated, ownership of MakerDAO is represented in the form of MKR tokens, also residing on a blockchain, which allow holders to vote on how the bank operates. MKR also provides holders with a claim on bank earnings. In effect, MKR tokens are like shares in Wells Fargo or Bank of Montreal. They are investments.

To regulate MakerDAO and the tokens associated with it – DAI and MKR – as gambling products just wouldn't make sense, for the same reason that regulating Wells Fargo or its underlying shares as a casino would be a clumsy fit.

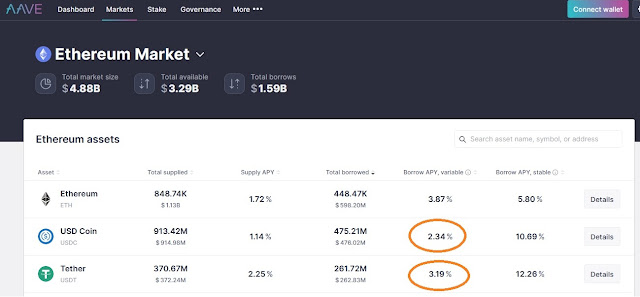

Or take decentralized tools Aave and Compound, which have been built on blockchains. Both are lenders. While these two tools certainly service a gambling clientele, they aren't themselves gambling apps and shouldn't fall into that category.

Or consider centralized exchanges such as Coinbase. Coinbase lets customers directly buy and sell crypto with cash, combining in one platform the roles of a traditional broker like E-Trade with a trading venue like Nasdaq. However, we apply securities regulation to E-Trade and Nasdaq, not gambling regulation, and should probably do the same for Coinbase.

In sum, to regulate crypto it'll take more nuance than just throwing it all into the gambling category. There are many different existing regulatory frameworks that can be applied to emergent blockchain-based products, of which gambling is just one.

Next, here’s what’s good about regulating crypto as gambling.

A long overdue recognition of crypto problem gambling

Dai, MKR, Aave and Compound may not be gambling. But a large proportion of crypto is gambling. That's because a big chunk of the people who engage with blockchains are doing little more than betting on the very volatile prices of first-generation unbacked volcoins like dogecoin, floki inu, and shiba inu. Let's not forget bitcoin, bitcoin cash, litecoin, xrp, and ether.

The crypto industry has tried its hardest to elevate volcoin betting from gambling to "investing." Coinbase, for instance, loftily sees its mission as to "increase economic freedom in the world."

But if you look under the hood, a volcoin such as dogecoin is little more than a never-ending 24/7 lottery on what average opinion thinks the price of dogecoin will be. This same recursive betting process is what drives the prices of bitcoin, litecoin and other volcoins. Users can sell their position in these never-ending lotteries to other players, and in some cases the casino chips get used as a payment token – but the payments functionality of volcoins has always run a distant second to their primary lottery function.

The benefit of officially recognizing volcoin-based betting as a form of gambling is that it would import into the world of crypto society’s already-existing protections for problem gamblers and children.

Problem gambling is a disorder characterized by a persistent and uncontrollable urge to gamble despite negative consequences or attempts to stop. It can lead to financial difficulties, relationship problems, and mental health issues such as depression and anxiety.

In many jurisdictions, gambling operators are required to address problem gambling by implementing self-exclusion programs that allow customers to voluntarily ban themselves from gambling establishments or betting sites. By regulating volcoins as gambling, venues that offer these products – say like Coinbase, PayPal and Kraken – would be required to set up exclusion programs of their own.

Gambling venues are often required by law to display responsible gambling messages such as "Play Responsibly. Remember, it’s just a game." The MegaMillions play responsibly page, for instance, provides information about problem gambling and a confidential 24-hour hotline.

Applying these messaging standards to crypto, it would no longer be permissible to represent volcoin purchases to clients as a form of investment. Rather, venues like Coinbase and PayPal would have to provide disclaimers along the lines as: "Play bitcoin responsibly. Remember, it’s just a game."

In many jurisdictions, a recognition of volcoins as gambling would limit opportunities for public advertising. In 2021, ads for floki inu flooded London. "Missed Doge? Get Floki," the ads said, appealing to peoples’ base fears of missing out. However, the United Kingdom has a very strict code surrounding gambling advertisements. Had floki and other volcoins been properly categorized at the outset as betting games, then floki’s advertising campaign would have had to pass many more hurdles.

Or take Matt Damon's notorious "fortune favors the brave '' ad for Crypto.com from early 2022. The ad tried to analogize volcoin buyers to intrepid explorers. By regulating volcoins as betting, ad creators could no longer draw these sorts of dubious analogies in an attempt to attract bettors to their platforms.

In particular, gambling regulatory frameworks in places such as the U.K. explicitly prevent gambling operators from reaching out to children through advertising. If volcoin betting were to be deemed a form of gambling, then crypto platforms that court users under the age of 18 (say like Block and Kraken have done in the past) would be required to put an end to this practice.

Finally, some U.S. states limit the ability of gamblers to fund their activities by credit, as does the United Kingdom. The idea is to prevent a problem gambler's addiction from snowballing into a much larger crisis for the family's finances. Translating this rule over to crypto could mean no longer allowing customers to buy volcoins with credit cards and/or restricting access to margin.