|

| Source: America Loves Crypto |

You may have recently come across the America Loves Crypto marketing campaign, sponsored by Coinbase, the U.S.'s largest crypto exchange. In an attempt to promote the voting power of crypto owners, the website makes the claim that 52 million American adults currently hold crypto, which constitutes 20% of the U.S. adult population. If true, that's a massive voting block.

As the source for its 20% statistic, Coinbase cites an online survey of 2,202 adults that it commissioned from Morning Consult last February, which among other questions queried respondents for how much crypto they currently hold.

If you've been following other sources for cryptocurrency adoption data, Coinbase's 20% statistic seems... questionable?

To see why, let's dig into U.S. crypto adoption data. What follows is a quick rundown of what the best surveys have had to say about Americans crypto ownership. Later on in the article I'll get into who they are, how much they own, and why they hold it.

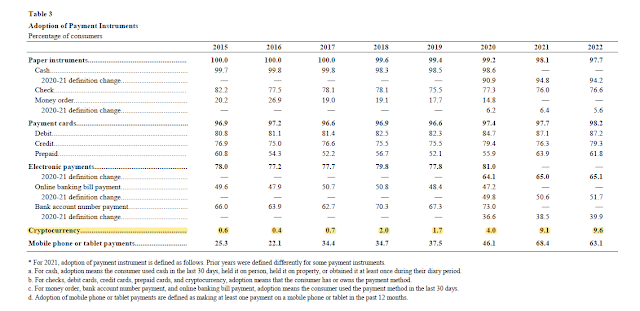

1) The granddaddy of all U.S. payments surveys is the Federal Reserve's Survey and Diary of Consumer Payment Choice, or SDCPC. The SDCPC is a long-running data collection effort that tries to paint a comprehensive picture of U.S. consumers' payment preferences and behavior. It fortuitously began to incorporate crypto-related questions way back in 2014, although crypto is just a tiny portion of the incredible amount of data collected by the SDCPC.

The Fed's SDCPC is run through the University of Southern California's Understanding America Study panel. In its 2022 iteration the SDCPC polled more than 4,761 participants. Notably, the SDCPC includes both a survey and a 3-day diary portion. Diaries are more labor intensive to administer than surveys, but provide better information since they minimize recall bias.

The SDCPC found that 9.6% of American adults owned cryptocurrency in 2022, up from 9.1% in 2021, and far higher than the 0.6% it polled back in 2015. However, that's far less than Coinbase's 20% claim. Only one of these numbers can be right. Which one is it?

The SDCPC's historical findings are in the table below.

|

| U.S. cryptocurrency adoptions rates. Source: Federal Reserve's 2022 Survey & Diary of Consumer Payment Choice |

2) The Federal Reserve publishes another survey that also sheds light on U.S. crypto adoption. The Fed's annual Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) examines the financial lives of American adults and their families, and is therefore more general than the Fed's SDCPC, which is focused exclusively on payments.

The Fed's SHED is administered by Ipsos using Ipsos's KnowlegePanel panel. In 2022, 11,667 participants completed the SHED.

The SHED only began to include questions about crypto in 2021. It finds that 10% of Americans used cryptocurrency during 2022, where "using" is defined as buying, holding, or making a payment or transfer with crypto. This amount was down from 12% in 2021 (see table below). The number of Americans who held cryptocurrency as an investment, a narrower definition than "using", fell to 8% in 2022 from 10%.

|

| Source: Federal Reserve's 2022 SHED |

The SHED's 8-10% number neatly confirms the SDCPC's 9.6% finding while disaffirming Coinbase's 20% statistic.

3) The next decent source for crypto adoption data is tabulated by a group of four economics and finance researchers using quarterly surveys of the Nielsen Homescan panel, comprised of 80,000 households. With response rates of 20-25% per survey, that represents data from 15,000 to 25,000 respondents.

Weber, Candia, Coibion, and Gorodnichenko (Weber et al) found that at the end of 2022, the fraction of all households owning crypto had risen to 12%. The black dotted line in the chart below shows how ownership rates have changed over time.

|

| Source: Weber et al (2023) using Nielsen Homescan Panel data |

4) The fourth in our survey of crypto surveys was conducted by the Pew Research Center using its American Trends Panel. In a March 2023 survey of 10,701 panelists, Pew found that 17% of American adults have "ever invested in, traded, or used" a cryptocurrency. This is a very broad category, and would presumably include someone who casually bought $25 worth of bitcoin back in 2015 and sold it three days later, and has never touched it again.

Drilling in further, of the 17% who have ever owned or used crypto, 69% report that they currently hold some, which works out to a 2023 ownership rate of 11-12% among American adults. That's not too far off the two Fed surveys and Weber et al, but significantly different from the Coinbase result.

5) A fifth source of data comes from Canada, which serves as a decent cross-check against U.S. data given that both countries are quite similar in terms of culture and geography. Of the two key Canadian surveys, the first is the Bank of Canada's long-running Bitcoin Omnibus Survey (BTCOS), administered by Ipsos, which amalgamates participants from three different panels.

The 2022 BTCOS polled 1,997 Canadians and found an ownership rate of 10%, down from 13% the year before (see chart below). This constitutes a lower bound to ownership rates since it only includes bitcoin owners. The 2022 BTCOS also finds that 3.5% of Canadians own dogecoin and 4% own ether. However, it's not possible to add these amounts to the 10% bitcoin ownership number since many respondents own multiple types of crypto.

|

| Source: Bank of Canada 2022 Bitcoin Omnibus Survey |

The second Canadian survey of note was carried out by the Ontario Securities Commission in 2022 to explore Canadian attitudes towards crypto assets. Conducted with Ipsos, the survey polled 2,360 Canadians in early 2022. It found that 13% of Canadians currently own any type of cryptocurrency, including crypto ETFs, which are legal in Canada but illegal in the US.

-----

So there you have it. The two Federal Reserve surveys put crypto ownership at 9.6% and 8-10% respectively in 2022, while Weber et al peg it at 12% using Nielsen Homescan data. Pew has American crypto ownership at 11-12% by early 2023. And in Canada, the Bank of Canada calculates bitcoin ownership to be at 10% by the end of 2022, while the Ontario Securities Commission pegs total crypto ownership at 13% in early 2022, before much of crypto imploded.

Given this range of data, the 20% adoption rate that Coinbase's Morning Consult survey trots out is a glaring outlier and probably deserves to be thrown out. The American crypto owner is a potentially sizeable voting group, but not as big as Coinbase would like us to believe.

For what it's worth, I've found a few other odd things with Coinbase's Morning Consult survey that further adds to my skepticism. Morning Consult reports that 8% of respondents currently own a cryptocurrency called USDC, down from 10% the quarter before (see here for more). The survey also says that 5% currently own Tether. USDC and Tether are stablecoins. To anyone who follows crypto closely, the idea that 1 in 10 Americans own any particular stablecoin is absurd. Given that Morning Consult has surely got this wrong, perhaps through a sampling error, that makes you wonder about the quality of their overall work.

However, even if we ignore Coinbase's Morning Consult survey, the 9.6% adoption rate found in the bellwether SDCPC is still breathtakingly high. In just fifteen years, crypto has gone from a strange niche product to something that is being held by tens of millions of Americans.

What additional facts do we know about America's crypto owners?

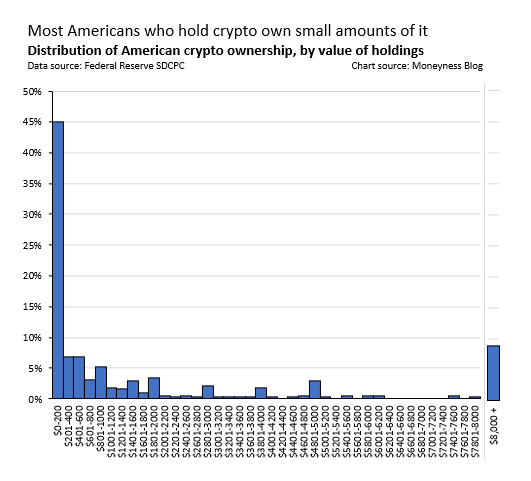

Size of holdings

Going through the SDCPC data, the majority of Americans who own crypto only have a little bit of the stuff. Out of all U.S. crypto owners surveyed, 45% owned just $0-200 worth of crypto in 2022. This is illustrated in the chart below. The median quantity of crypto held was $312. Given such small amounts, I doubt that these crypto owners qualify as durable crypto adopters, as opposed to folks who've jumped on the bandwagon when they saw a Superbowl ad from Coinbase, bought some dogecoin, and have since stopped paying any attention.

The SDCPC data suggests that 1 in 4 crypto owners are what I call crypto fundamentalists, holding more than $2,000 worth of crypto. Given that 90% of Americans don't hold any crypto at all, two in every 100 Americans qualifies as a crypto fundamentalist.

This skewed distribution of crypto ownership is confirmed by survey results from Weber et al and the Nielsen Homescan panel. An outlier group of hard-core owners, representing around 8% of all crypto owners, allocates their entire portfolio to crypto (see chart below). By far the largest group of crypto owners is comprised of small dabblers who put just 0-5% of their portfolios into crypto.

|

| Source: Weber et al (2023) using Nielsen Homescan Panel data |

Reasons for ownership

Why do Americans own cryptocurrency? Despite being labelled as "currencies," cryptocurrencies are not generally used as a medium for making payments. Price appreciation is the dominant motivation for owning them.

When the SDCPC survey queried participants in 2022 for their "primary reason for owning virtual currency," the most popular answer (at 67%) was investment (see chart below, orange rows). The second most popular reason (21%) was "I am interested in new technologies." It was rare for respondents to list any sort of payments-related use case as their primary reason for ownership. As for lack of trust in banks, the government, or the dollar – all of which are common cryptocurrency themes – these were rarely mentioned in 2022 as a primary reason for ownership.

Interestingly, Americans crypto owners were not always so obsessed with price appreciation. In 2014, the SDCPC found that American crypto currency owners tended to offer a much broader set of motivations for owning crypto, including lack of trust, cross-border payments, and to make purchases of goods and services (see chart above, blue rows).

The dominance of investment as the motivating reason for owning crypto is echoed in Weber et al's analysis of Nielsen Homescan survey data. Respondents were allowed to give multiple reasons for owning cryptocurrency, the most popular reason (see chart below) being to take advantage of "expected increase in value." The desire to use cryptocurrencies for international transfers was almost nonexistent, as was the desire to be "independent of banks."

Crypto owners don't care about making international transfers, private purchases, or being "independent of banks," as the chart shows.

— John Paul Koning (@jp_koning) June 22, 2023

What they want is "increase in value."

This is a fairly reliable data source: 80,000 households participating in the Nielsen Homescan Panel. pic.twitter.com/0oBfATgFoY

The Fed's SHED survey isolates the same pattern as the other two surveys (see table below). Of the 10% of Americans who report using cryptocurrency in 2022, most do so as an investment. One small difference is that the SHED reports that around 2% of all survey participants used crypto to send money to friends of family in 2022. This suggests the transactional motive, while not primary, may be somewhat more prevalent than the previous two surveys suggest.

|

| Source: Federal Reserve's 2022 SHED |

Types of cryptocurrency held

What sorts of crypto were popular with Americans? Using Nielsen Homescan data, Weber et al found that of the 11% of survey

respondents who are crypto owners, 70% held bitcoin while just over 40%

held ether and dogecoin respectively.

Around 11% of American households owned crypto in 2021, according to a Nielsen Homescan survey of 80,000 households.

— John Paul Koning (@jp_koning) July 4, 2023

Of this 11%, 4 out of 10 households held Dogecoin.

So around 6 million US households owned Dogecoin in 2021, which is just nuts. pic.twitter.com/31FjTbfqBE

This distribution is echoed in the Fed's 2022 SDCPC. Almost 65% of all crypto owners surveyed held bitcoin (the data is here), making it the most popular type of cryptocurrency. Meanwhile, 44.8% held ether and 38% held dogecoin, a coin that was originally created as a joke in 2013. That works out to around 4-5% of all Americans who are in on the joke.

Crypto bros

There's a reason that people throw around the term "crypto bro." Without exception, all of the U.S. surveys find that cryptocurrency owners tend to be young, male, and have a high income.

The same goes for Canada, where in 2022 there were three male bitcoin owners for every female. The Bank of Canada has also regularly tested bitcoin owners for their degree of financial literacy using the Big Three questions method, and finds that they tend to have lower financial literacy than non-bitcoin owners.

Interestingly, in addition to isolating the crypto bro pattern – the tendency for crypto owners to be young, male, and wealthy – both the Pew survey and the Fed's SHED (see table below) find that U.S. crypto owners are more likely to be Asian, followed by Black and Hispanic, and least likely to be White.The prototypical Canadian bitcoin owner in 2022 was a young university-educated male, employed at a high-income job, and lacking financial literacy. pic.twitter.com/N3hQX4AWes

— John Paul Koning (@jp_koning) September 28, 2023

The Fed's SHED survey dug deeper into usage by demographics, and found that while "investment" remains the driving case for owning crypto, and that the rich use the stuff proportionally more than the poor, certain demographic groups tend to rely on it more than others for making transactions. Specifically, the SHED finds that among low income families, 5% report an investment motivation for holding crypto while 4% report a transactional motivation.

|

| Source: Federal Reserve's 2022 SHED |

All of this data suggests to me the existence of three American crypto archetypes.

The most dominant crypto archetype is the young wealthy male crypto dabbler, most likely non-white, who holds a few hundred bucks worth of doge or some other coin in order to gamble on prices going up. Coinbase's America Loves Crypto campaign makes the claim that "the crypto owner is a critical voter," but I suspect this doesn't hold for the dominant dabbler archetype, who probably doesn't have much attachment to their casual $50 bet on doge or litecoin or bitcoin, and thus can't be assembled into a voting block for crypto-related cause.

Another archetype is the much rarer crypto fundamentalist, a young male who has committed most of his savings to crypto. I suspect these are the types I encounter on Twitter, who evangelize and debate crypto to anyone who'll listen. This may be a small group, but they are also the most likely to vote for crypto-related causes.

Lastly, there seems to be a very small group of low-income people who are using crypto for actual transactions, the original use-case that Satoshi Nakamoto intended when he introduced the first cryptocurrency back in 2008.

.JPG)