Now that the U.S. debt ceiling season is upon us again, I've been wondering if the U.S.'s official gold price is going to finally be revalued from $42.22. Why so?

Since March the U.S. Treasury has been legally prohibited from issuing new debt. Because the government needs to continue spending in order to keep the country running, and with debt financing no longer an option (at least until the ceiling is raised), Treasury Secretary Mnuchin has had no choice but to resort to a number of creative "extraordinary measures," or accounting tricks, to keep the doors open. Here is a list. They are the same tricks that Obama used in his brushes with the debt ceiling in 2011 and 2013.

The general gist of these measures goes something like this: a number of government trusts and savings plans invest in short term government securities, and these count against the debt limit. As these securities mature they are typically reinvested (i.e rolled over). The trick is to neither roll these securities over nor redeem them with cash. Instead, the assets are held in a limbo of sorts in which they don't collect interest—and no longer count against the debt limit. This frees up a limited amount of headroom under the ceiling that the Treasury can fill with fresh debt in order to keep the government functioning.

These tricks provide around $250-300 billion of ammunition. Which sounds like a lot, but in the context of overall government spending of $3.7 trillion or so per year, it isn't. Most estimates have the extraordinary measures only lasting till September or October at which point a default event may occur, unless Congress raises the ceiling.

Not on the official list of measures for finessing the debt ceiling is a rarely-mentioned option that I like to call the gold trick. The U.S. government owns a lot of gold. Beware here, because a few commentators think that the idea behind the gold trick is to sell off some of this gold in order to fund the government. Nope—not an ounce of gold needs to be sold. The only thing that the Treasury need do is raise the U.S.'s official price for gold. By doing so, it automatically gets "free" funding from the Federal Reserve, funding which doesn't count against the debt ceiling.

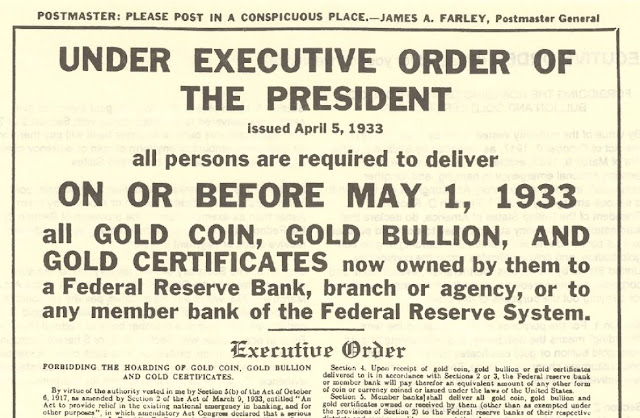

We need a bit of history to understand the gold trick. Back in 1933 all U.S. citizens were required to sell their gold, gold certificates, and gold coins to the Fed at a rate of $20.67 per ounce. This is the famous gold confiscation that gold bugs like to talk about (see picture at top). The 195 million ounces that the Fed accumulated was subsequently sold to the Treasury. In return, the Treasury provided the Fed with gold certificates obliging the Treasury to pay them back. At the official price of $20.67, these certificates were held on the Fed's books at $4 billion.

The certificates the Fed received were a bit strange. A gold certificate usually provides its owner with a claim on a fixed quantity of gold, say one ounce, or 1/2 an ounce. In this case, the certificates provided a claim on a nominal, not fixed, amount of gold. If the Fed wanted to redeem all its certificates, it couldn't ask the Treasury for the 195 million ounces back. Rather, the certificates only entitled the Fed to redeem $4 billion worth of gold at the official price.

As long as the yellow metal's price stayed at $20.67, this wasn't a big deal. But it had important consequences when the official gold price was changed, which was exactly what happened in January 1934 when President Roosevelt increased the metal's price from $20.67 to $35. At this new price, the stash of gold held at the Treasury was now worth $6.8 billion, up from $4 billion. But thanks to their odd structure, the value of the Fed's gold certificates did not adjust in line with the revaluation—after all, they offered little more than a constant claim on $4 billion worth of gold. The remaining $2.8 billion worth of gold, which had been the Fed's just a month before, was now property of the Treasury.

Almost immediately the Treasury printed $2.8 billion worth of fresh gold certificates, shipped these certificates to the Fed, and had the Fed issue it $2.8 billion in new money. Voila, the Treasury had suddenly increased its bank account, and it didn't even have to issue new bonds, raise taxes, or reduce program spending. All it did was change the official gold price.

(If you want find this description confusing, I explained the gold trick slightly differently in 2012.)

---

Even when the U.S. eventually went off the gold standard—unofficially in 1968 and officially in 1971—it still maintained the practice of setting an official gold price. But by then the official price was no longer the axis around which the entire monetary system turned; it was little more than an accounting unit.

As gold's famous 1970s bull market started to ramp up, the authorities tried to keep pace by enacting changes to the official price. When gold hit $55 in May 1972, the official price was bumped up from $35 to $38. They ratcheted it up again in February 1973 to $42.22, although by then gold's market price had advanced to $75. Both of these revaluations resulted in the Fed providing new money to the Treasury, just like in 1934. Albert Berger, a Fed economist, has a good description of these two events:

A 1974 Fed analysis of the effects of raising the official gold price: https://t.co/XP2pka1YoR & my old blog post: https://t.co/G1SLGD6QTH pic.twitter.com/QDdMIsxVLK— JP Koning (@jp_koning) January 9, 2017

After the 1973 revaluation the government stopped trying to keep up to gold's parabolic rise, and to this day the U.S. maintains an archaic price of $42.22, far below the actual price of $1250 or so.

---

Let's bring this back to the present. Come October, imagine that the U.S. Treasury has expended all of its conventional extraordinary measures and Congress—despite having a Republican majority—can't decide on increasing the debt ceiling. Desperate for the cash required to keep basic service open, Treasury Secretary Mnuchin turns to an archaic, long forgotten lever, the official gold price. Maybe he decides to change it from $42.22 to, say, $50, or $100, or $1000—whatever amount he needs in order to fund the government. The mechanics would work exactly like they did in 1934, 1972, and 1973. The capital gain arising from a rise in the accounting price would be credited to the Treasury in the form of new central bank deposits, and these could be immediately deployed to keep the government running.

Any change in the official price of gold needs to be authorized by Congress. Why would the same Congress that can't agree on adjusting the debt ceiling or repealing Obamacare agree to Mnuchin's request to change the price of gold? The Republican party has a long history of advocating for the gold standard; Ronald Reagan, for instance, was a supporter. President Trump himself likes the yellow metal. If you believe him, he once made a lot of money off of it:

Donald Trump, gold speculator. "It's easier than the construction business." https://t.co/3bgcGgo4Yn pic.twitter.com/khBOELaiEH— JP Koning (@jp_koning) November 29, 2016

As for the Republican's base, many of them are keen on ending the Fed—anything that smells of a return to gold will make them happy. This seems to be a piece of legislation that pleases all factions.

The gold trick only works because the debt issued by the Fed—reserves, or deposits—is not included in the category of debts used to define the debt ceiling. By outsourcing the task of financing government services to the Fed via gold price increases, the Treasury can sneak around the ceiling. This is only cosmetic, of course, because a debt incurred by the Fed is just as real as a debt incurred by the Treasury, and so it should probably be included in the debt ceiling. After all, the taxpayer is ultimately on the hook for debt issued by both bodies.

An increase in the price of gold to its current market price of $1250 would only be a band-aid. While it would provide the Treasury with around $315 billion in new funds from the Fed, this would be enough to evade the debt ceiling for just a few months, maybe half a year. Sure, a few well-time Donald Trump tweets about the greatness of gold might push the price up by $50 to $1300, but even that would only buy the Treasury an extra $13 billion or so in central bank funds.

---

The Fed would hate the gold trick.

Much of Fed policy over the last few years has involved communicating with the public about the future size of the Fed balance sheet, which shot up over three rounds of quantitative easing. A sudden $315 billion increase in liabilities outstanding due to a revaluation of the official gold price to $1250 would throw a wrench in this strategy. To the public, it would look QE4-ish.

QE is reversible. Unlike QE, the Fed would not be capable of reversing a balance sheet expansion caused by a gold revaluation, at least not without the Treasury's help. This would severely damage the Fed's independence. To see why, keep in mind that the Fed can only ever increase the money supply if it gets an asset—a bond, mortgage backed securities, gold, etc—in return. The advantage of having an actual asset in the vault is that it can be sold off in the future should a constriction in the money supply be necessary. Assets also generate income which can be used to pay the Fed's expenses like salaries or interest on reserves. With the gold trick, however, the Fed is being asked to increase the money supply without receiving a compensating asset. This means that, should it be necessary to drastically shrink the money supply in the future, it will only be able to do so by relying on goodwill of the Treasury. So much for being able to act independently of the President.

That the Fed probably prefers that the Treasury avoid a gold revaluation is one reason that it has never become one of the go-to extraordinary measures for finessing the debt ceiling. But I'm not sure that the current administration is one that cares very deeply about what the Fed thinks. If Congress greenlights the revaluation, there's really nothing that Fed Chair Yellen can do except enter-key new money for Mnuchin.

---

Earlier I mentioned that adjusting the official price to $1250 would only be a band-aid solution. Here's a bit of speculative fiction: imagine that come October the official price is adjusted up to something like $2000, or $5000, or $10,000. Granted, this would put it far above the market price of $1250--but the official price has been wrong for something like fifty years now; does anyone really care if the error is now to the upside rather than the downside?

At an official price of $10,000, for instance, the Treasury would get some $2.6 trillion in spending power from the Fed, enough for it to avoid issuing new t-bills and bond in excess of the debt ceiling for several years. The Republicans would save face; they could tell their constituents that they held firm against an increase in the ceiling. When the Democrats--who are no friends of gold--inevitably come back to power, they could simply go back to the tradition of jacking up the debt ceiling.

This would certainly be a strange world. During Republican administrations, bond and bill issuance would slow dramatically, reserves at the Fed expanding in their place. Like the various QEs, there is no reason that these reserve expansion would cause inflation. The Fed would have to be careful that it pays enough interest on reserves that banks prefer to hoard their reserves rather than sell them. This increase in the Fed's interest burden would dramatically crimp its profits, which are paid out as a dividend to the Treasury each year. In fact, all the money the Treasury saved on not paying t-bill and bond interest would be almost precisely cancelled out by a shrinking Fed dividend. There is not much of a free lunch to be had.

Investor who like to hold government debt in their portfolios would be in a bit of a jam. Everyone can buy a t-bill, but the ability to hold reserves is limited to banks. Unless the Fed were to allow wider access to their balance sheet, Republican administrations resorting to the gold trick would create broad safe asset shortages.

While a small increase in the official gold price may be part of Mnuchin's backup plan, a large increase to the official gold price is just speculative fiction. After all, a boost in the official price of gold to $10,000 would create an entirely different monetary system. Alternative systems are certainly worth exploring for what they teach us about are own system, but one would hope that the actual adoption of one would come after long debate and not as a result of opportunistic politics.

P.S. After writing this post, I stumbled on a paper by Fed economist Kenneth Garbade which describes how Eisenhower finessed the debt ceiling by using a version of the gold trick. Unlike 1972 and '73 the gold price was not increased. Instead, the Treasury was able to make use of unused space from the 1934 revaluation. A large portion of the gold the Treasury owned had not yet been monetized by writing up gold certificates and depositing them at the Fed. In late 1953, with the debt ceiling biting, around $500 million in gold certificates were exchanged with the Fed for deposits.

The " Gold Trick " only works because the official price is below the market price. The other way round and the Fed would not be able to partake in it, as its balance sheet would become impaired , as, if it cashed in the certificates to hold the physical gold on the asset side, the asset side at market price would not suffice to cover the liabilities issued against them.

ReplyDeleteI'm not following you.

DeleteIf the Fed sold the gold it would get the market price, unless it sold to the treasury. If the Treasury wants to contractually undertake to pay more than the market price then it can do so , but that part of the contract would be the same as a zero coupon bond , ie it would be a debt and would contribute to the national debt as a zero coupon bond.

Deleteie.

Gold market price = $300 Treasury gold Certificate $600 = $300 gold price plus $300 zero coupon bond.

The Fed can only get the premium from the treasury and so the gold itself is immaterial to the contract. Its a plain contractual IOU a contractual bond to pay a sum of money in return for a previously advanced sum of money.

In fact ,on second thoughts , in that scenario the debt is the entire $600 because there exists an ongoing obligation of the Treasury, the obligation of the Treasury to present the Fed with the money specified and take back what was being used as collateral in what is a repurchase agreement.

DeleteAccording to investopedia.com a repurchase agreement is treated as debt for accounting purposes.

And that makes sense as otherwise any short term loan of money where the lender takes hold of collateral, would not be a debt either. The characteristic feature is the existence of the contractual obligation to buy back.

Sorry, I'm still not following you.

Delete"If the Fed sold the gold it would get the market price, unless it sold to the treasury."

The Fed can't sell the gold. It doesn't own any gold, it owns non-marketable gold certificates.

Ah well in that case it is more simple, the cash for gold certificates is a debt at any mandated gold price chosen. As the certificates are a claim on gold, and so the Treasury has a debt of Gold to the Fed.

DeleteThe General case when a borrower has an asset to same value as the debt they are still in debt. A mortgagor has a debt although the house has the same value as the cash obtained from the mortgage transaction, or when someone has $100 from a bank in return for an undertaking to pay the bank $100 at a later date and holds that $100 in their pocket the transaction outstanding is still a debt. The treasury has an outstanding undertaking to present the Fed with gold and so that is debt.

I see your idea has the government unilatearlly defining the size of the Feds gold assets above the market price , but for that to have a practical consequence would require that the relevant agents scrutinising the balance sheet joined the pretence. The international central banks , the bond market, the general public, the Forex and so the gold trick would not work.

Delete"...unilatearlly defining the size of the Feds gold assets above the market price."

DeleteNot the Fed's gold, the gold in the Treasuries vaults.

"...would require that the relevant agents scrutinising the balance sheet joined the pretence. The international central banks , the bond market, the general public, the Forex and so the gold trick would not work."

No one has to "join the pretence." All the U.S. government is modifying is an internal accounting price, one that is solely relevant to two institutions, the Fed and the Treasury.

Its not internally between the Fed and the Treasury. If the deposit holders of a bank don't have confidence in the valuation of a banks assets or don't consent to the valuation of the banks assets the consequence is a run on the bank in the case of a commercial bank or hyperinflation in the case of a central bank.

DeleteA bank is an arrangement where the depositors have the claim on the banks assets. The benefactors of the banks assets are the deposit holders. For it to viable The depositors have to consent to the valuation of the assets.

The issue of constraints on shrinking the Fed balance sheet is only relevant down to the level of central bank notes outstanding (plus a few other minor items such as capital and the standard minimum level of Treasury balances and bank reserve balances roughly at the pre-QE level).

ReplyDeleteIn other words, the balance sheet can’t be shrunk down to a size that is smaller than at least the level of central bank notes outstanding, plus those other entries that are less material in value.

So there is no constraint to shrinking the balance sheet to the minimum possible level, provided that non-marketable assets don’t exceed the sum of those liability items, most of which would be bank notes outstanding. If that's the case, there will be sufficient marketable assets such as Treasuries and Agencies available to shrink the balance sheet down to that minimum size, if so desired.

The written up value of gold or claims on gold would be one of those non-marketable assets.

(It certainly is an asset – just not one that is typically used in open market operations. Gold is gold and claims are claims. Assets.)

In addition, one of the things that’s happened over the lifetime of QE is that central bank notes outstanding have actually increased. That means that less than 100 per cent of QE needs to be reversed in order to return the balance sheet to a comparable pre-QE profile (assuming other things such as Treasury deposit balances and reserve balances return to roughly their pre-QE level).

Treasury balances created by a gold revaluation would soon end up as new bank reserves and those bank reserves could subsequently be drained by QE reversal along with the rest.

So a gold revaluation in theory shouldn't be a material constraint on shrinking the balance sheet, assuming some reasonable real world related choice for the new value.

"So a gold revaluation in theory shouldn't be a material constraint on shrinking the balance sheet, assuming some reasonable real world related choice for the new value."

DeleteI agree. If the choose a whopping gold price for the new value (i.e. $10000) you'd start getting constraints.

Fascinating post. It seems like the combination of:

ReplyDeletea) please the republican base

b) unshackle Treasury from periodic debt ceiling debates

c) reduce fed independence through the "back door"

makes this at least worth a serious kick of the tires from the administration's point of view

I'm not so sure if "The mechanics would work exactly like they did in 1934, 1972, and 1973". In 1934 the US was externally on a gold standard - in 1971 and 1973 it wasn't. When foreigners wanted to sell gold at $35 in 1934 the US gov was obliged to buy and pay in USD. The USD for the trade left the US as the exchange was: foreigners exported gold to the US, the US exported USD abroad.

ReplyDeleteIn the seventies zero (monetary) gold entered the US. In 1934 - 1949 the US government bought 18,518 tonnes of gold from abroad.

Yes, you're right.

DeleteWhat I meant to say by that is like in 1934, 72, and 73, the capital gains created by the rise in gold's price would be entirely appropriated by the Treasury.

JP, this is a strange post. Strange, because I seem to find three quite substantial things I disagree on. I'll probably end up agreeing with you, but not without some good explanations from your side.

ReplyDeleteDinero and JKH, both of whom I respect highly due to my earlier encounters with them, have already touched two of the three issues. But I don't see you having addressed the issues in your replies to them, so here we go.

I start with the first one.

You said: "With the gold trick, however, the Fed is being asked to increase the money supply without receiving a compensating asset."

Following JKH, I must ask: Why not an asset?

You say that the Treasury is not obliged to exchange the certificates for gold -- for now. Fine. But let's say the Treasury sells all its gold to investors abroad. Will the Fed continue to hold those gold certificates like nothing has happened? Aren't the "gold certificates" certificates of gold ownership, even if the Fed accepts that it is not able to take possession of the gold as it pleases?

"You said: "With the gold trick, however, the Fed is being asked to increase the money supply without receiving a compensating asset.""

DeleteI probably could have phrased it better. If the gold price was ratcheted up to $1250, the Treasury could create gold certificates (up to the difference between the old and new value of gold in Treasury vaults) and bring these certificates to the Fed to be monetized i.e. used as collateral for deposits. And these certificates would certainly be assets.

These aren't great assets to have, since they are non-marketable, the Fed needs the permission of the Treasury to redeem them, and their real value falls when the official gold price is increased. Far better to get a t-bill or bond, both of which could be more effectively mobilized should it be necessary to reduce the money supply. But yes, gold certificates are assets.

Thanks, JP! We agree on that, then.

DeleteI'd like to point out that the real value of the certificates is not really relevant for the Fed, as the RHS of its balance sheet -- as does most of the LHS -- consists of nominal (value) items only.

What does probably matter, though, -- and this takes us to my second disagreement with you, an issue first pointed out by Dinero -- is that the nominal value of the certificates doesn't exceed the nominal market value of Treasury's gold. Although, if that was the case, I think we must assume that the difference between the (higher) book value of the certificates and the (lower) market value of Treasury's gold would be public debt; comparable to coins in Fed's possession: zero-coupon and without defined maturity.

What do you think?

"I'd like to point out that the real value of the certificates is not really relevant for the Fed, as the RHS of its balance sheet -- as does most of the LHS -- consists of nominal (value) items only."

DeleteWhat I mean by "their real value falls" is that when the official gold price doubles, the market price staying constant, each certificate has a claim on just half the quantity of gold ounces, and is therefore worth half as much. And this makes them a dodgy asset for the Fed to own.

As for your second point, I don't know where you're going with it. It will help if you copy the exact phrase from my blog post that you disagree with.

Sorry, JP. I wrote in a hurry yesterday. Here's one of your phrases related to what I'm talking about (see also Dinero's comments above):

Delete"Granted, this would put it far above the market price of $1250--but the official price has been wrong for something like fifty years now; does anyone really care if the error is now to the upside rather than the downside?"

This is actually getting really interesting. This is a hard subject, and it touches accounting related to coins (incl. the famous trillion dollar coin), both from Treasury's and the Fed's point of view. I'm working on a longer reply, but as a heads-up, I'll post two links:

Link 1: Treasury Financial Manual, Chapter 2000: ISSUANCE AND REDEMPTION OF GOLD CERTIFICATES

Link 2: COINS AND

CURRENCY: How the Costs and Earnings Associated with Producing Coins and Currency Are Budgeted and Accounted For

I wouldn't be surprised if you have read those. Have you? Anyway, it's essential for our discussion that we understand the subject matter of these documents. For instance:

"Gold certificates represent a Treasury liability to the FRB since the FRB has loaned cash to the Federal Government with gold as the collateral. Liabilities incurred by issuing gold certificates are limited to the gold being held in the TGA at the standard (par) value established by law."

Source: Link 1 (p. 1)

"The profit earned from making coins, or seigniorage, is shown in the budget as a means of financing the government’s borrowings and is not counted as revenue in calculating the deficit or surplus for the annual budget. Seigniorage reduces the government’s requirement to borrow money from the public to finance the debt. Although the profit earned from making coins adds to the government’s cash balance, it does not involve a payment from the public, which is considered a receipt."

Source: Link 2 (p. 12)

"Seigniorage on coins should be shown as “other source of financing” in Treasury’s Consolidated Statement of Changes in Net Position, as provided for in the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board (FASAB).7 However, Treasury has been accounting for seigniorage as a reduction in the net cost of operations in its Consolidated Statement of Changes in Net Position. Although Treasury’s net cost of operations has included seigniorage as a reduction in costs, seigniorage had not been separately labeled in the statement."

Source: Ibid (p. 14)

As the last quote testifies, there's been substantial confusion regarding the accounting treatment of coins, and I'm not 100 % sure whether that confusion has been finally cleared or not. What bothers me is that they talk about only the seigniorage (face value of coins minus minting costs) being a source of financing, although I'd prefer to view the full face value of the coins as a source of financing (an increase in public debt, that is).

Well, that was already a long reply, so I'll save you from another :-) Instead, we can take this bit by bit.

DeleteLet's stay with the gold certificates for now. Are they really certificates of gold ownership (gold which the Fed, funnily enough, is safekeeping on behalf of Treasury?), or are they actually more traditional IOUs with Treasury's gold acting as collateral (as the Treasury Financial Manual suggests)?

If the latter is true, then we can think of this as a case of over-collateralized loans/IOUs. And in that case, Treasury issuing new gold certificates after increasing the official gold price just means that it is taking on more debt by using the same, plentiful collateral.

This also means that the gold certificates are far from dodgy assets for the Fed -- quite the contrary. Sure, they are non-interest-bearing assets. But then again, so are Treasury bonds when the Fed is concerned, as it will remit the interest paid by Treasury back to Treasury.

JP said to Dinero: "All the U.S. government is modifying is an internal accounting price, one that is solely relevant to two institutions, the Fed and the Treasury."

DeleteHere might be the key to this riddle. You are probably right in what you say above. If that's true, it in my view just proves the point I and Dinero are trying to make: The gold certificates are really just IOUs/bonds. Should Treasury set the official price at $3,000 and issue certificates to match the nominal value of the gold stock calculated at that price, it would mean the actual collateral is inadequate / the loan is partly un-collateralized.

So, it might be that they could set the official price well above the market price. And perhaps the increased debt wouldn't be counted towards the debt ceiling (although it clearly should).

Nevertheless, this wouldn't add up to "an entirely different monetary system" as you claim in the last paragraph of your post -- unless what you mean by that is a system where the Treasury would be allowed to sell bonds directly to the Fed (not only indirectly as it does now)?

The link to the "trillion dollar coin" I hinted at should be obvious by now. That, just like the gold certificates, would be a de facto Treasury liability in the Fed's books, bearing no interest and having no defined maturity. (Much like Adair Turner's perpetual zero-coupon bonds, with the difference that in his helicopter money / "overt monetary financing" vision Treasury would commit to NEVER redeem those bonds.)

"Should Treasury set the official price at $3,000 and issue certificates to match the nominal value of the gold stock calculated at that price, it would mean the actual collateral is inadequate / the loan is partly un-collateralized."

DeleteLet's work through the accounting. Say the market price of gold is $20 but the official gold price is $10. The Treasury has 10 ounces in its vaults which it officially values at $100. Many years ago it monetized all this gold by providing the Treasury with 10 gold certificates. So the Fed's balance sheet has $100 in gold certificates on it.

Now the official price of gold is doubled to $20, everything else staying the same.

The Treasury still has 10 ounces in its vaults which it now values at $200. The Fed's certificates still provide it with $100 worth of gold, but this has now shrunk to a claim on just 5 ounces ($100/$20). This means that where before all of the gold in the Treasury's vault had been monetized, now only 1/2 of it is. The other 5 ounces is unencumbered and belongs entirely to the Treasury. Maybe it keeps the gold. Maybe it sells it to China. But if the Treasury does what what it did in 1934/72/73, it will proceed to monetize this gold by bringing $100 worth of certificates (i.e. 5 ounces x $20) to the Fed as collateral for $100 in newly created deposits.

Next it raises the price to $30, the market price still being at $20.

The Treasury still has 10 ounces in its vaults which it now values at $300. The Fed's certificates provide a claim on $200 worth of gold, or 6.666 ounces. The remaining 3.333 ounces is now unencumbered and belongs to the Treasury, which can monetize this gold by bringing $100 worth of certificates to the Fed (i.e. 3.3333 ounces x $30) as collateral for $100 in newly created deposits.

Where is the problem?

If the deposit holders of a bank don't have confidence in the valuation of a banks assets or don't consent to the valuation of the banks assets the consequence is a run on the bank in the case of a commercial bank or hyperinflation in the case of a central bank.

DeleteA bank is an arrangement where the depositors have the claim on the banks assets. The benefactors of the banks assets are the deposit holders. For it to viable The depositors have to consent to the valuation of the assets, and that consent would not be forthcoming.

JP, I see two problems in your example:

Delete1. It might be hard to get an official price of $30 accepted, when the market price is $20. Treasury generally follows accounting standards, and those include something known as "prudence concept" which says that one should be conservative when valuing assets. If I remember correctly, the US GAAP specifically says that one should write down fixed assets when their fair value (in this case, market price) falls below their book value (the official price), but that you shouldn't write up fixed assets when the opposite occurs (which might partly explain why Treasury hasn't written up the value of its gold stock -- this is a long shot, I admit).

2. If $30 price was nevertheless accepted and the gold was fully monetized, this would lead to a problem related to gold sales by Treasury. Let's say Treasury sold half of its stock, 5 ounces, to China at $20 market price. Total price $100, credited to Treasury's account at the Fed (TGA). Treasury would now need to redeem half of the Fed's gold certificates, at total price of $150 (5x$30), debited to TGA. It would need to cover the $50 extra debit by, say, taxation.

Hi Antti Jokinen

DeleteMy Observation is

No 1 . The basic gold certificate arrangement is still a debt as it is a repurchase agreement

and repurchase agreements are treated as debts, as according to investopedia.com for example.

No 2. As you and I discussed on a previous post comments the Deposit holders are the claimants on the banks assets and Pricing the Asset at above the the market value is an attempted trick on the Deposit holders, which would not be accepted by them.

The Gold trick is called a TRICK and so its not surprising the conceit of the trick can be identified if the trick is scrutinised.

Dinero,

DeleteI'm inclined to agree with you, but I'm afraid this is not that straight-forward. What are the assets the Fed is valu(at)ing here? Is it gold or is it a partly collateralized (assuming official price > market price) Treasury liability? If it's the latter, then I, as a FR note-holder, would have no objections -- assuming the sums we are talking about are not outrageous. For instance, Treasury might explain that this is a temporary solution to avoid technical insolvency caused by the debt ceiling, and will be reversed once the ceiling is lifted.

If it wasn't said to be temporary, and the sums were significant, then I'd ask why are they doing this instead of selling debt to the public. After all, this is nothing else than selling debt directly to the Fed, which is not permitted in the case of bonds.

By the way, do you find any real difference between JP's "speculative fiction" and the "Trillion Dollar Coin"? I don't. Both gold certificates and coins are Treasury/government liabilities without defined maturity (coupon, zero or not, doesn't matter if only the Fed can hold them), and why they are not subject to the debt ceiling is beyond me.

(My reply above is to your earlier comment, Dinero.)

DeleteI see your point. The the "gold certificate fiction" is not a Repurchase agreement because the the liability of the Treasury is the gold itself.

DeleteIt is still a debt, as a contract where the the party that receives money pledges to deliver a commodity is a debt. It impairs the Feds balance sheet for the Federal reserve note holders because the fed liabilities, the Fed notes , HAVE ALREADY BEEN ISSUED on the asset valuation at the previous price.

But Treasury doesn't pledge to deliver gold? Instead, it issues debt in form of "gold certificates" (these are relics which today have very little to do with gold). It could as well sell bonds (perpetual, if you want full comparability) or coins (as it does all the time, through the Mint) directly to the Fed. The effect would be the same. No?

DeleteThis is why I don't see any impairment of balance sheet.

Yes the treasury does make that pledge.

DeleteQuote from the post '' the gold certificates provide a nominal not a fixed amount of gold''

The impairment to the balance sheet is because the liabilities are less than the assets .

Taking the arbitrary re evaluation after the fact of the issue of fed notes to the ultimate conclusion of its internal logic , the certificates give the fed a claim on ZERO gold. That illustrates the absurdity.

Dinero, this is directly from the Treasury (see my earlier comment to JP):

Delete"Gold certificates represent a Treasury liability to the FRB since the FRB has loaned cash to the Federal Government with gold as the collateral."

As I said, the certificates have very little to do with gold. A claim on zero gold, as you say. Instead, they are directly comparable to coins, which are Treasury-issued currency, and should be viewed as public debt. Coins/currency are no claims on some fixed amounts of anything, either. Yet they are, to their holders, some kind of nominal claims (on goods priced at $10, say).

Coins don't give the Fed any claim on gold, yet you don't see that they would impair its balance sheet, do you?

Antti,

Delete"1. It might be hard to get an official price of $30 accepted..."

In general I agree. It's too weird. That's one reason I called the idea speculative fiction. Raising it to $900 or $1000 isn't so weird.

"2. If $30 price was nevertheless accepted and the gold was fully monetized, this would lead to a problem related to gold sales by Treasury..."

If all of the newly unencumbered gold was monetized, i.e. used to collateralize an issue of new Fed deposits, then why would the Treasury bother conducting subsequent gold sales? It already got what it wanted; free money to get around the debt ceiling. As long as it doesn't sell any gold, the Treasury need never redeem the Fed's gold certificates (which as you say would require the taxpayer to eventually step forward.)

Why don't gold certificates count towards the debt ceiling? I don't know. The 1974 Fed paper implies that they don't, and Eisenhower somehow avoided the debt ceiling in 1953 using a version of the gold certificate trick. I'm just accepting it on their authority.

If the 1974 paper was wrong and Eisenhower broke the law, there is still a version of the gold trick that works. Reprice gold up to $800 or $900, then sell the unencumbered metal directly into the market rather than monetizing it with the Fed. But that path isn't as smooth.

Considering the two quotes which are pretty definitive

Delete"The act of changing the official dollar price of gold, under

the situation in recent years where the United States has not bought or sold gold at the official price, does *not* by itself have monetary consequences. However, *subsequent* transactions between the Treasury and the Federal Reserve do have important monetary effects"

And the Treasury manual

" FRB has loaned cash to the Federal Government with gold as the collateral."

The money in debt to the Fed is not reduced by upping the official price of gold after all, as the gold its collateral only, the actual loan is a sum of cash and the debt remains the same size of the cash sum. It would only affect future transactions.

It would be a debt , although easier to repay than one that is expected to be repaid via tax receipts rather than the physical asset that is already in Treasury inventory.

Coins are a different matter , the situation where the Treasury mints coins where the face value is not the metallic value is legal and well established and it works quite well. If a commercial bank was to carry coins as an asset they would be equitable in the accounting to the same extent that deposit holders would value them in their own physical possession. But if the Fed was to accept them as assets the resulting Fed notes would be more like " Greenbacks."

I dont see coins "should be treated as public debt". As the GAO quote states They are a government asset.

They dont have any feature of debt.

Dinero said: "The money in debt to the Fed is not reduced by upping the official price of gold after all, as the gold its collateral only, the actual loan is a sum of cash and the debt remains the same size of the cash sum."

DeleteI agree.

On coins I don't agree. First, I don't find any GAO quote saying coins are government assets. They are Fed assets when in its possession (see balance sheet). But so are Treasury bonds.

GAO says that seigniorage related to coins should be reported as "other source of financing". How should we interpret this? Aren't bonds a source of financing as well? (My current understanding is that the full face value of coins should be reported as a source of financing, if we want to be consistent.)

There are still some old Treasury notes (the cash version, comparable to Fed notes) in circulation. Like coins, these were issued by Treasury. Like coins, they are assets to the Fed if in its possession. Like Fed and Treasury notes, coins can be used to pay taxes -- and can, or at least could, be issued when the government wants to make purchases (MMTers, among others, would say that this makes them government IOUs?).

As I said earlier, coins are a hard subject and there is significant confusion around them. It took me a while to make sense of them, and still I'm not sure if others see them in the same way as I do. Anyway, the way I view them forms a part of a coherent whole -- to me :-)

I'd be happy to hear JP's thoughts on this.

JP, I think we're mostly on the same page now.

DeleteYes, it wouldn't be weird to raise the official price in a conservative way. I used to think the Fed owned the gold outright (people often talk about its gold stock, not stock of certificates?), and I remember thinking that it could easily re-value that stock should, for instance, equity turn slightly negative. I still think we are quite safe thinking as if the Fed owned it outright, and that any re-valuation would then affect directly its "owner's" (I know this is slightly more complicated in the case of the Fed; thinking about central banks generally) position, whether through equity or Treasury's account.

Overall, as you also seem to suggest, the situation is this: gold is a strategic asset for the US government, and it is reluctant to sell it (it wouldn't go smoothly, as you put it). Yet, due to historical reasons (otherwise, why not create "real estate certificates" and encumber other government property?) it probably views it as some kind of semi-money available to be spent, and that's why it is still used as collateral to effect spending. But in my view this just blurs the situation: what is actually a loan/debt (the substance) is easily mistaken for something else (gold certificates; the form).

I still need to read the 1974 paper. Will get back to you later.

I said: "Yet, due to historical reasons... it probably views [gold] as some kind of semi-money available to be spent, and that's why it is still used as collateral to effect spending."

DeleteMy hunch above seems to get confirmed by the 1974 paper (p. 3):

"Treasurv cash holdings, which include non-monetized gold...

The Treasury does not buy goods and services directly with gold. The Treasury disburses its payments for goods and services from its accounts at the Federal Reserve Banks. Hence, the Treasury converted the increased dollar value of gold, a non-spendable item, into a spendable item, deposits at the Federal Reserve Banks."

Again, the Treasury doesn't buy goods and services directly with buildings, either. Yet we don't talk about converting them, or their increased dollar value, into a spendable item, do we? This language would be understandable if the Treasury sold it to the public, so that it ended up in private ownership. But selling it to the Fed (and not even selling it outright, but using it as collateral/repoing it/whatever) means that the gold remains in common ownership (the public commonly owns it), just like it is when it is "owned" by the Treasury.

I replied to you in the 'digital money' thread. I'm afraid this post is too technical for me to catch up with, seeing that I'm late to the party. But from what I can tell, I'm on the same page with you (and everyone else :-)).

DeleteIn general, I find the the debt ceiling discussion a giant distraction. IMO the focus should not be on how much is being spent, but primarily on what it is that government is spending on. By answering the latter question, the former answers itself and becomes superfluous.

I suppose playing around with accounting is as worthy a pastime as any other. But quite frankly, if Congress wanted to find to spend more, they'd just raise the debt ceiling. No need for additional 'tricks' or help from accounting wizards - or only to the degree that tricks can fly below the radar. The real question is: why don't they want to? And indeed, should they? And on what? I don't think accounting offers any answers to these larger questions.

> Antii

DeleteThe GAO says that the Treasury sells coins to the Fed at the face value of the coins and that transaction reduces interest payments on debt to the Fed.

But to put it more simply, The Treasury sells coins to the Fed at face value ,and if it did not have debts with the fed, it would receive Fed notes which it could spend. That what makes coins a face value asset for the Treasury.

Dinero, let's assume the Treasury was allowed to sell bonds directly to the Fed. If you now replace 'coin' in your comment with 'bond', then what's the difference? I don't see any difference, yet Treasury bonds are definitely not an asset for the Treasury. Interest payments are not relevant here, because the Fed will remit those back to the Treasury.

DeleteThe difference is a bond needs to be repaid. That is the difference.

DeleteMake that bond perpetual (a consol). An asset for the Treasury? The same applies to gold certificates, which look much like perpetual, zero-coupon bonds. (Note that 'perpetual' means it doesn't need to be repaid, but it can be repaid. That's why I often talk about debt without defined maturity.)

DeleteThere is no connection with debt. The coins are SOLD to the Fed. There is no outstanding obligation.

DeleteMy understanding of coins is that they are a liability of the Treasury. For instance, we might imagine that the quarter starts to lose value such that one quarter only buys four nickels, and it takes five quarters to get a $1 bill. It's the Treasury's obligation that the proper exchange ratio (1 quarter to 5 nickels, 4 quarters to 1 dollar bill) prevails, not the Fed's. It will have to buy back quarters en masse to fix this.

DeleteThat being said, I don't know exactly where that liability is listed. It pops up in the H.4.1 statement as "Treasury currency," [link] but I don't see it on the Treasury's actual balance sheet.

From JP's link:

Delete"Coin and paper currency (excluding Federal Reserve notes) held by the public, financial institutions, Reserve Banks, and the Treasury are liabilities of the U.S. Treasury. This item consists primarily of coin, but includes about a small amount of U.S. notes--that is, liabilities of the U.S. Treasury--that have been outstanding since the late 1970s. U.S. notes are no longer issued."

It's not that straightforward nor intuitive, so I understand well Dinero's standpoint. As the GAO report showed, up until 2002 the Treasury used to report seigniorage as revenue in the budget, even though it should have reported it as a source of financing. (As I said earlier, I still don't understand why only seigniorage -- face value less minting costs -- is considered a source of financing, and not the full face value of coins.

I might be wrong, but I think that in this discussion we are already very close to the limits of the current understanding related to coins/other Treasury liabilities among any experts.

The only way I can see that the existence of the coins represents a "liability" to the Treasury is in a cost to be incurred after the coin is issued, in providing a replacement coin to a person who presents a worn out coin to the treasury for replacement. And so when the treasury issues some coins it undertakes the "liability" of replacing them a later date when they wear out. Which I suspect is the case.

DeleteWhat about English tally-sticks or U.S./Treasury notes, how do you view them? Government liabilities or not? I think they are fully comparable to coins, though much cheaper to produce.

DeleteThe UK had treasury issue more recently than English Tally sticks. In 1914 there were Bradbury notes. There are pictures of then on the BoE website.

DeleteTally sticks and Treasury notes and coins, they are not Liabilities.

Dictionary.com definition of liabilities

Liability

noun, plural liabilities.

1.

liabilities.

a) moneys owed; debts or pecuniary obligations (opposed to assets ).

When the treasury buys something with a coin or treasury note it does not incur on the Treasury further "moneys owed" as of course the money has already been consigned.

On the subject of Gold, here is something to ponder, if a Central bank had a significant amount of gold would the value of its notes fluctuate, particularly on the forex when the gold price fluctuated.

"The only way I can see that the existence of the coins represents a "liability" to the Treasury is in a cost to be incurred after the coin is issued, in providing a replacement coin to a person who presents a worn out coin to the treasury for replacement."

DeleteIt's far more than that. When Canada withdrew the 1 cent coin a few years back, we didn't just throw them in the street. We brought them back to banks, which in turn sold them at par to the government. So 1 cent coins were always a liability of the Canadian government--one that only became apparent when it had use tax revenue and/or issue bonds to fund the redemption of 1 cent coins.

Good example, JP!

DeleteDinero: I agree no money is owed. Money itself is about goods and services owed, although the claim is to a nominal "amount" of goods (whatever costs, say, 10 dollars), just like in the case of gold certificates.

Likewise, in your gold example above, the value of notes would not fluctuate, because they are claims on a nominal amount of goods/assets; equity fluctuates assuming assets are marked to market.

JP, as in your Canada example, the US Treasury's account (TGA) is debited when FRBs redeem U.S. Notes:

Delete"5040.10d—Transaction D: U.S. Notes and Silver Certificates Redeemed and Destroyed by FRBs--

CCB authorizes FRB Richmond to charge the TGA for the amount of U.S. notes and silver certificates redeemed and destroyed by the FRBs." [link]

The effect is identical with a case where the Treasury has to redeem a maturing Treasury bond/note/bill in the Fed's possession. This proves that U.S. notes (comparable to coins) are a Treasury liability in the same way as Treasury bonds are: it redeems both with "cash" charged from the TGA.

Btw, I still haven't found coins on US government's financial statements. It doesn't look like they report them as liabilities, even though they say that coins are liabilities.

> Antii

Delete" goods and services owed. "

The coins carry no obligation for the government to supply goods and services to the holder of the coins.

> JP

DeleteThe withdrawal is the same as the replacement for worn out coins , as the government could have compensated the public with one five cent coin for every 5 of one cent coins withdrawn. That did not happen, maybe for convenience.

Overall the government will make a profit on the withdrawal of the one cent coin, if , for every 5 of one cent coins the banks sold to the government , the banks go on to to buy 1 five cent coin from the government.

It costs less than 5 cents to produce a five cent coin and the mint will also get the melt value of the one cent coins.

In the UK we are replacing all £1 coins this year.

Antti: Good find, U.S. notes seem to work the same way. You can see that they are also included in the definition of Treasury cash, which is in the earlier link I posted. Earlier when I was doing research for this post I found it interesting that neither U.S. notes nor silver certificates count to the debt ceiling.

DeleteDinero: "as the government could have compensated the public with one five cent coin for every 5 of one cent coins withdrawn. That did not happen, maybe for convenience."

That did not happen. Canadians certainly have a demand for small change, but by 2013 the penny did not satisfy any part of that demand; it was considered useless. So when Canadians brought in their three or four rolls of pennies, they did not need a substitute, say 60 or 80 nickels. Rather, they asked to either get money credited to their bank accounts, or large denomination cash.

In this paper, the Canadian senate estimates the buyback would cost around $100 million.

If a 5 cent coin was not to be the chosen settlement by the policy it could have been a larger coin, a dollar or two dollar coin for 100 or 200 pennies. A coin for a coin seems reasonably appropriate.

DeleteIn the paper the melt value is taken into consideration reducing the cost to $50 million.

As I said it also needs to be take into consideration the fact that the demand for 5 cent coins will increase an so that revenue to the Treasury needs to be taken into consideration. As you say Canadians have a demand for small change. Transactions that were done in 5 pennies will now be done in 5 cent coins.

Dinero said: "The coins carry no obligation for the government to supply goods and services to the holder of the coins."

DeleteNo, they don't. The obligation is usually fulfilled by the taxpayer, who needs currency to be able to settle his taxes. Although it might be fulfilled by the government which sells public assets. To see how this all works requires that one views the monetary system as a record-keeping system for this kind of nominal debts of goods and services (nominal, because a $10 debt doesn't define any real amount of goods owed).

As a rule of thumb, if on the LHS of the central bank balance sheet there is an item which has a face value (which is higher than the intrinsic value of the item) -- in other words, it's a nominal item -- then it is a record of someone's liability to give up goods and services. Treasury bonds, gold certificates, coins, MBSs, etc. Most importantly, public debt is the public's liability -- not the government's liability, per se. Public debt is reduced through taxation (= taxpayers, ie. members of the public, and not the government, pay the debt by giving up goods and services).

I'm writing a longer blog post on how this all works.

JP, yes, it bothers me that they are part of Treasury cash. It's like a casino reporting the full face value of chips in its possession as assets, while saying, correctly, that chips in circulation are its liabilities -- without reporting them as its liabilities (subject to debt ceiling). You see what I mean?

DeleteThis might be a daring thing to say, but I think this is a reporting error which is due to lack of understanding when it comes to Treasury currency. (This is understandable, though, because there is no agreement about what a "government liability" really means -- see my comment to Dinero above.)

Regarding GAO report on coins, this is how in my view coins should be accounted for:

DeleteThe Mint should not receive any revenue from selling the coins. The Fed "buys" the coins as Treasury liabilities, just like it buys gold certificates. It should credit the TGA, just like any bank credits a loan customer's -- which in this case is the Treasury, not the Mint -- checking account after having received the customer's IOU.

In the consolidated government budget, the minting costs should be reported as expenditures. The full face value of coins (and gold certificates, for that matter) should be reported in the same way as newly issued Treasury bonds are reported.

A case could be made for reporting the bullion/intrinsic value of the coins as assets, though. This is because as records of a liability, the coins could be viewed, in a way, as physical property of the Treasury. (Chips are property of the issuing casino, aren't they?)

I said budget, but what I really meant is financial statements. I just thought that it's more conventional to talk about government budget even in this case :-)

DeleteHi Antii

DeleteSee JP's comment " neither U.S. notes nor silver certificates count to the debt ceiling."

The coins are not a component of the government debt, and so you cannot use the context of a debt on a balance sheet in describing them.

When they appear on a central bank balance sheet , they are the same as gold bars on the balance sheet because of the governments particular legal right to mint coin an mandate the value there of. The government does not have an obligation to sell public assets due to the issue of the coins, unlike a person who issues a loan contract, who does have an obligation to sell something and so a liability.

The is no obligation on the public either.

All you can say is there needs to be enough public and government commerce in the economy to maintain the value of the total issue without inflation. But that is not a liability.

Hi Dinero,

DeleteWhen we look at things from an alternative viewpoint, coins ARE part of public debt (the Treasury doesn't say without a reason that they are Treasury liabilities).

If I remember correctly, you agreed that coins are comparable to U.S./Treasury notes or tally-sticks? (You said none of them are liabilities to the entity that issues them.)

Here's how it all works in my world, using U.K. Treasury notes as an example:

I sell two sacks of flour to the government. Price £5. The Treasury issues a £5 note and gives it to me. That's a credit (in third-party records; in my own books it would actually be a debit) to me, telling that I've given something worth £5 without getting anything, yet, in return.

The government took something worth £5 without giving anything in return. The government accountant records a £5 debit in its books on an expenditure/purchases account: "Two sacks of flour bought". How did it finance this purchase? By issuing a note and giving it to me. That's a £5 credit entry to account "Notes in circulation". On a balance sheet, that would be on the RHS (liabilities).

I say that this £5 is public debt. This is how the public pays it back:

My neighbour owns some cattle. The government decides to collect cattle tax from him, worth £5. So, my neighbour sells me beef priced at £5 and receives the note from me. I was supposed to receive something worth £5 in exchange for my flour, and now I did. My neighbour, being part of the public, was supposed to give up something worth £5 to repay some public debt. He did.

What we are used to call "paying taxes" is only the record-keeping part of the transaction. The accounts are updated when my neighbour walks into the tax office and hands over the £5 note to the taxman. As a consequence, the government accounts are updated: a £5 credit entry on "Cattle tax collected" account (this revenue is netted against the earlier expenditure) and a £5 debit entry on "Notes in circulation" account. (The Treasury might as well burn the note at this point; it's no asset to it, as it can issue new notes at virtually no cost.) Public debt is reduced by £5, because I as a note-holder got beef from my neighbour, a member of the public. My neighbour doesn't receive anything to compensate him for the beef -- that's called repaying a debt --, as he had to give up the note.

Remember: This is an alternative viewpoint, something you can try to adopt if you will. I'm happy to clarify. I'm writing a very long post on all this, but it might take some time before I'm done.

Coins seem to me to be a subdivision of paper or deposit currency. The initial creation of both coins and paper/deposit currency should have the same basic source.

ReplyDeleteWhat is that source?

Let's go heuristic here.

Money is created when banks lend money. Hence, when central banks lend money to governments, money is created.

When governments borrow money from central banks but never pay it back, the money supply must increase to the limit of money borrowed. "Never pay it back" should be read as never recapturing and destroying the money created when the initial loan was taken. Instead, government rolls debt over, increasing the amount owed to the central bank.

Governments do not necessarily borrow from banks. Government can also borrow from private citizens who come into possession of money government has previously borrowed. This borrowing forms a mechanism to limit the amount of cash money actually in circulation (which aids in maintaining the value of money relative to other physical goods).

Government can also get funding from taxation. Taxation and borrowing from the public have the identical effect on the cash money supply available to the public. Taxation avoids debt funding to the extent of taxes collected.

I think MMT would assume that central banks are arms of government. I would agree. This explains why the central bank would willingly lend and re-lend to government without limit. Money can be created as required by government, disguised as debt.

The fact that coins are directly created by government does not change this basic scheme. Only the middle-man (the central bank) has been eliminated.