Cash isn't quite anonymous, it's anonymous-ish.

To illustrate this, a few years ago I wrote about the 1932 Lindbergh kidnapping case. The ransom was paid in gold certificates, not Federal Reserve notes. By coincidence, the U.S. went off the gold standard the next year, and all gold certificates were called in. So when the kidnapper spent some of his gold certificates in 1934 to buy gas, his purchase was odd enough to out him to the authorities.

I recently stumbled on a more recent example of cash de-anonymization. Most people know the gist of the Watergate scandal, but to recap five burglars were caught breaking into Democratic headquarters at the Watergate building on June 17, 1972.

Who were they and what were they doing there? At first, no one had a clue. But the police did find around $3,600 in cash on them, much of it in sequentially-numbered $100 banknotes. See the serial numbers below:

| Testimony of Paul Leeper, May 1973, Hearings Before the United States Congress, House Committee on the Judiciary [source] |

A series of sequential banknotes meant that the cash had come fresh from the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the agency that produces banknotes on behalf of the Federal Reserve. The new notes would have been sent to a bank which in turn distributed the notes in their original sequential order to customers.

The serial numbers of the Watergate notes also gave a geographical sense of where they had been issued. There are 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks. Notes beginning with F are issued into circulation by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, those beginning with C by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

Two days after the break-in, FBI agents contacted these two district banks for more information. It turns out, Federal Reserve Banks do keep track of banknote serial numbers. The Philadelphia Fed informed agents that the notes in question had been shipped to a private bank, the Girard Bank & Trust in Philadelphia, while the Atlanta Fed had shipped theirs to the Republic National Bank in Miami.

Unfortunately, the two commercial banks did not record the serial numbers of the bills that they had distributed to the public. However, one of the burglars--Bernard Barker--happened to have an account at the Republic National Bank in Miami. (The trail to the Girard Bank & Trust turned cold).

Scanning through Barker's bank information, investigators discovered that several months before five large deposits had been made into his account. This included four checks totaling $80,000 drawn on a Mexico City bank and one for $25,000 from a Miami bank. These funds were eventually traced back to the the Committee to Re-Elect the President, an organization created to help raise funds for Nixon's upcoming election campaign.

And there was a smoking gun. A money trail from the pockets of the Watergate burglars to the President's administration. The burglars, it was further discovered, had been hired by Committee to Re-Elect the President to wire-tap Democrat party phones and photograph documents. So the President was spying on his political enemies.

----------

There is an interesting sidebar to this story. Two days after the break-in, Senator William Proxmire, chairman of the Financial Affairs Subcommittee, contacted the Fed for information about the banknotes. In a book published in 2008, economist Robert D. Auerbach accused Arthur Burns, Nixon's appointee to lead the Fed, of refusing to cooperate with Proxmire's requests. Presumably Burns wanted to protect his boss.

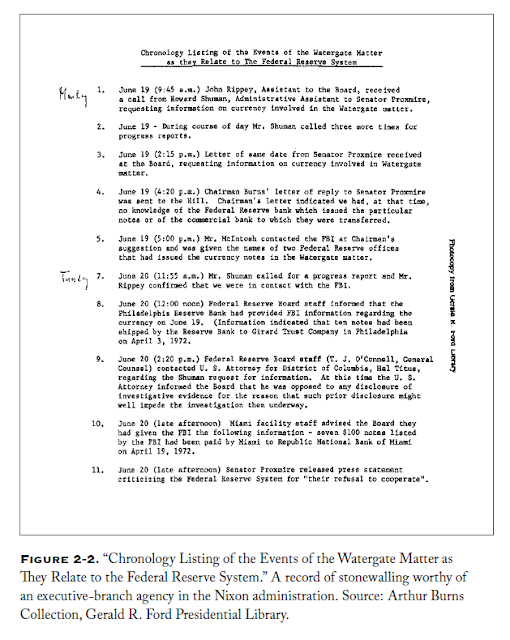

In his book, Auerbach cited the following internal document, a timeline of the Federal Reserve Board's actions after the Watergate break-in. It is available in the Arthur Burns papers in the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library:

Congressman Ron Paul aired Auerbach's allegations in front of Congress in 2010. An investigation was soon initiated by the Office of the Inspector General, an independent body that conducts oversight and audits of the Federal Reserve. In 2012, the OIG exonerated Arthur Burns and the Fed. The report noted that Burns was complying with FBI requests to avoid sharing the information lest this interfere with the investigation.

----------

So banknote users are never entirely anonymous--the serial numbers can be used to unveil who they are. In Watergate's case it was a fairly blunt tool. The notes could only be traced to the burglar's Miami bank, not to his account. But if tellers at the Republic National Bank had been dutifully recording the serial numbers of notes they gave to their customers, the tool would have been much more accurate, pinpointing Barker as the direct source of the Watergate banknotes.

No bank teller want to tediously record numbers by hand. But in today's world, it is technically possibly for ATMs to record banknotes using built-in serial number readers. Is this actually happening? I am pretty sure that serial numbers are not being collected by North American banks. People would be furious about potential invasions of privacy.

But not so in China. Since 2013, Chinese ATMs and tellers are required by law to record the serial numbers of all banknotes. (I am not sure if the same law applies to Hong Kong):

Even cash can be tracked. The Chinese government has required bank tellers and ATMs to record & log banknote serial numbers since 2013: https://t.co/dxZHRGAOHi pic.twitter.com/kCILa5ndOR— John Paul Koning (@jp_koning) December 26, 2019

I snipped the above screenshot from a marketing brochure from Glory Ltd, a Japanese company that specializes in cash handling technology. Chinese laws surrounding banknote serial number collection have ostensibly been put into place to prevent counterfeit yuan from entering into circulation. But one could imagine this technology being used by the authorities to track licit money flows.

Say that a Chinese human rights activist deposits ten ¥100 banknotes into their bank account. The police might be curious about who is financing this activist. In theory, they could ask the People's Bank of China, the nation's central bank, to search the various serial number databases for the name of the owner of the bank account from which the ten ¥100 notes originally came. In this way an anonymous cash donation could be de-anonymized.

Chinese citizens who use cash in potentially risky transactions have probably already devised a solution. They can evade serial number sniffing by going through an extra step of "mixing" their cash prior to spending it. This might involve breaking up the notes in a few shops prior to passing them on to the intended recipient. Of course, this trick will only work as long as retailers are not required to install their own note-reading hardware.

I often write about the contradictions of anonymous payments. It would have been great to catch Nixon's thugs with technology that completely de-anonymizes banknote movements. But it is abhorrent to know that human rights activists might be prosecuted using this same technology. Striking a balance is difficult.